Understanding the Impact of Trauma and Effective Treatment

Does trauma change the brain? If you have been through a traumatic event, you might experience significant differences between how you responded to a stimulus before trauma and how you might respond now. Post-traumatic stress disorder can cause significant changes to brain structures and neurotransmitters.

If you or a loved one are suffering from trauma, Catalina is here to support effective recovery.

Catalina Behavioral Health takes a holistic approach to your healing and wellness. We know that symptoms from sleep disturbances to hypervigilance can likely be traced back to a trauma response.

Keep reading for more information on the brain and trauma, and we would be honored if you choose to allow us to help begin a healing journey with our evidence-based trauma treatment programs.

Get a Confidential Trauma and PTSD Assessment – Call Now!

Trauma Affects Changes in the Prefrontal Cortex

The first and one of the most significant areas affected following a traumatic event is the prefrontal cortex. Those individuals diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often have reduced capabilities in this area, which results in an increased fear response.

Normal brain development can often regulate the triggers to negative experiences, but PTSD symptoms limit this capability. Alterations in the prefrontal cortex can limit your ability to regulate emotions, make key decisions, and focus on the task at hand. If you have significant changes to the prefrontal cortex, all of these will become problematic.

How is this part of the brain impacted in trauma survivors?

Most researchers believe that a flood of stress hormones known as catecholamine is realized when a traumatic event takes place. From here on out, a trigger will repeat the increase in stress hormones. This results in major changes in the prefrontal cortex and its ability to help you make sound and rational decisions.

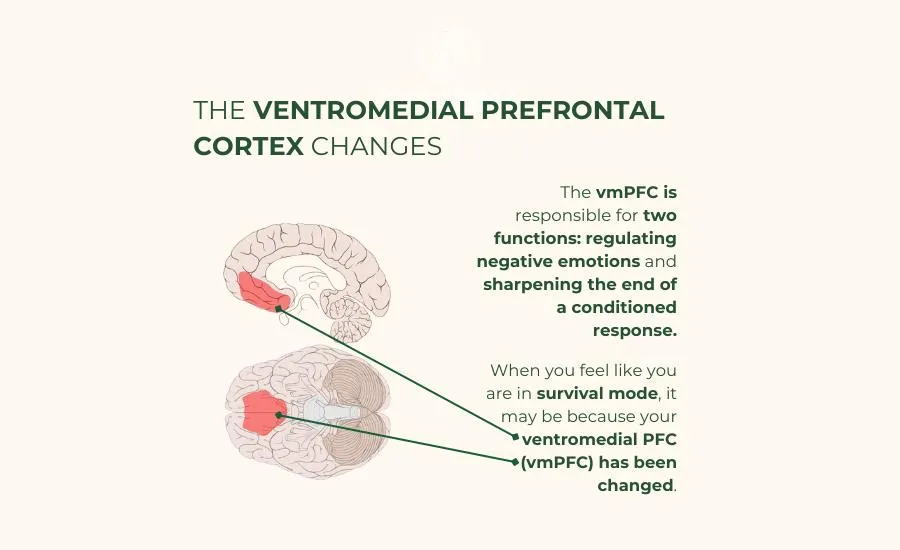

Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex Changes

Of course, it is too simplistic to say that the PFC is impacted by a change in brain chemistry. When you feel like you are in survival mode after trauma has disrupted your life, it may be because your ventromedial PFC (vmPFC) has been changed.

The vmPFC is responsible for two functions: regulating negative emotions and sharpening the end of a conditioned response (also known as extinction).

On brain imaging scans, those who have post-traumatic stress disorder tend to have less active vmPFC. The research does not necessarily indicate a cause-and-effect relationship with damage to this area of the brain. It does, however, seem to indicate that damage to the vmPFC is the result of long-term distress caused by PTSD symptoms.

Extinction is an important component to look at concerning the vmPFC and a traumatic event. This part of the nervous system is responsible for extinction. When impaired, it may be less likely to trigger that response and will continue to initiate stress hormones when a trigger arises.

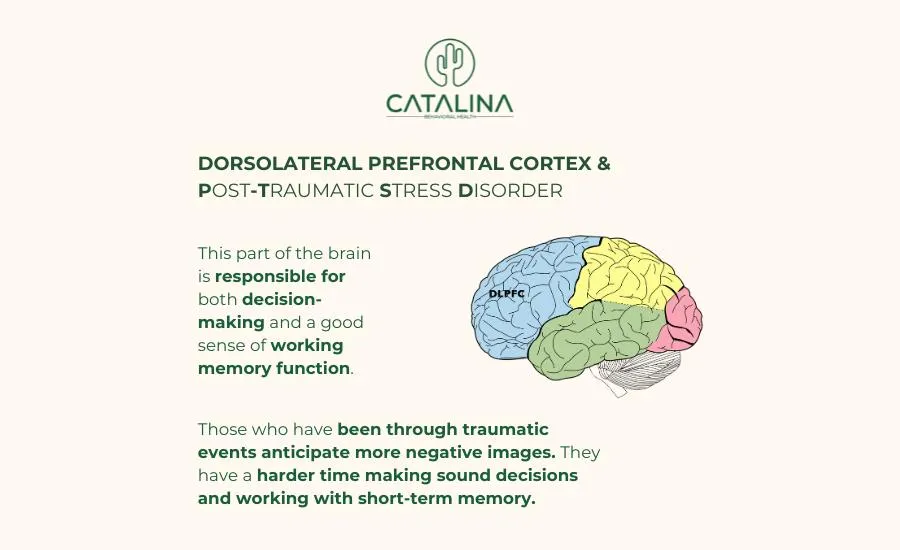

Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Changes in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

The brain is perhaps one of the most complex organs of the body and its role on the entire nervous system is significant. In addition to changes in the vmPFC, the dorsolateral PFC also sees significant changes in PTSD patients. This part of the brain is responsible for both decision-making and a good sense of working memory function.

What happens to it when posttraumatic stress disorder enters into the picture?

Some research shows that those who have been through traumatic events anticipate more negative images. They have a harder time making sound decisions and working with short-term memory. Most people who have less severe PTSD symptoms tend to have greater activation of the dorsolateral PFC.

Mid-Anterior Cingulate Cortex Differences

While the prefrontal cortex might be the first place to think about when mental disorders are at play, the mid-anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is another important component that faces substantial changes in those with PTSD. The ACC has a role when it comes to processing emotions and regulating autonomic body processes.

Unfortunately, the ACC is typically less thick when measured in those who have post-traumatic stress disorder. What does that mean when it comes to how the brain processes emotions?

ACC abnormalities predict greater symptoms associated with automatic processes in the body such as your heart rate, breathing, and other psychophysiological responses. It becomes much harder to keep a handle on some of these things when exposed to a perceived threat.

Changes to the Limbic System in PTSD

The limbic system is one of the most significant aspects of brain structure, and it suffers significantly when trauma occurs. In particular, there are two parts of the limbic system impacted by posttraumatic stress disorder: the amygdala and the hippocampus.

Amygdala Changes Impact Emotional Processes

First, consider what the amygdala does for the brain without trauma. This robust yet very tiny piece of your brain structures includes important activities like:

- Assessing potential threats in your environment

- Storing and consolidating memories

- Conditioning your fear responses

Changes to the amygdala are significant and are caused by an overactive amygdala following traumatic events like natural disasters or assaults. In particular, it leads to a sense of hypervigilance which is one of the symptoms of PTSD. It causes you to be in a constant state of edginess and nervousness, never sure whether a situation is safe.

An overactive amygdala also causes you to be less discriminatory in what is deemed a threat. You may respond to more mundane threats as life or death instead of routine occurrences.

Hippocampus for Memory Storage

In addition to the amygdala, the other part of your triune brain model contains the hippocampus. The hippocampus is responsible primarily for two things: moving memories from short-term to long-term storage and managing stress hormones. In those who develop PTSD, the hippocampus tends to be a bit smaller.

One of the first ways that the developing brain is impacted by PTSD is via the stress response regulated by the hippocampus. Patients with PTSD often have higher levels of cortisol which is released by this region of the brain.

However, that is not the only distinction made by the hippocampus when posttraumatic stress disorder is at play. It can also make it more likely that you will have intrusive thoughts and memories about an event that dramatically impacted you. You may start to see similarities everywhere as your brain tries to process what took place.

Get Immediate Help for Trauma and Mental Health – Reach Out Now!

Brain Stem Changes for Automatic Responses

In addition to how trauma changes the brain, your brain stem will also play a new role after you have experienced trauma. The brain stem is responsible for relaying messages from the various parts of the brain to the rest of the body. Most often, it is associated with automatic processes like keeping your heart beating or regulating your breathing.

When other brain areas are overactive and start telling your body to respond to a threat, it is the brain stem that coordinates the effort.

It is part of your reptilian brain and does very little thinking of its own. Instead, it simply responds to events as other parts of the brain tell it to, regardless of how viable and serious those threats are. An overactive brain stem can lead to increased blood pressure, heart rate, breathing rate, and more.

Changes to the Rest of the Nervous System

Of course, there are two other systems associated with the brain that can have an impact on your stress inoculation in the aftermath of trauma. Take a closer look at how the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems are changed by a traumatic experience.

Differences in the Sympathetic Nervous System

When it comes to the nervous system, brain development is not the only thing that needs to be weighed in a PTSD diagnosis. The sympathetic nervous system (part of the autonomic body processes) suffers just as much as changes to the limbic system and PFC.

In clients diagnosed with PTSD, it seems that the sympathetic nervous system is often in a constant state of hyperarousal. This condition primes your body for a response to a threat and helps survival instincts to kick in. Some of the symptoms that your sympathetic nervous system is overactive include:

- Increased heart rate

- Increased blood pressure

- Faster breathing

- Difficulty regulating body heat (hyperthermia)

In other words, the sympathetic nervous system is responsible for triggering your fight-or-flight response to trauma.

These symptoms can make it hard for you to rest and recategorize traumatic events, making everyday triggers into life-or-death situations. You will find it extremely difficult to soothe yourself with your sympathetic nervous system in overdrive.

Parasympathetic Nervous System and Calming

The parasympathetic nervous system is also strongly impacted by exposure to trauma. As you have already seen, the sympathetic part of your nervous system is responsible for the activation of fight-or-flight responses. The parasympathetic nervous system is designed to calm those urges to enter into battle or flee from a stressor.

The problem is that your brain may have a harder time issuing the parasympathetic response after it has been exposed to trauma. It can take more time for it to respond correctly and to calm you down.

To get the parasympathetic nervous system to function faster, you may need to equip yourself with new coping skills. Mindfulness and other dialectical behavior therapy skills such as meditation can help you calm down the body, as can other treatments like prolonged exposure therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy.

Can Medications and Therapy Correct Brain Changes After PTSD?

One of the most pressing questions surrounding posttraumatic stress disorder is whether those physical changes to the brain can be corrected with therapy or medication. The good news is that the brain is highly plastic, meaning that it can change and evolve as you do.

Just because your reptilian brain is impacted by trauma now does not mean it will always have the same effect on you.

SSRIs for Neurotransmitter Levels

Because of the changes in brain structure, you may also experience changes in brain chemistry with your neurotransmitters. This is why selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are one of the first-line treatments for PTSD symptoms. It can even lead to remission of symptoms altogether. However, psychiatry is not the only field you might consider for PTSD treatment options.

Prolonged Exposure Therapy and Cognitive Processing Therapy

Prolonged exposure therapy is another means of engaging the brain and learning that not every trigger is a threat. This therapy tends to bolster communication between the vmPFC, amygdala, and hippocampus while increasing activity in the dorsolateral PFC. This helps regulation in response to fear symptoms and supports fear extinction.

Cognitive processing therapy is also an important component of your healing. This will allow you to take a closer look at how your thoughts and feelings impact your actions. By interrupting the cycle early, you may find that you can alter your actions and reactions to trauma triggers.

All of these treatment options can be used together for lasting changes and profound effects.

Heal Your Brain After PTSD at Catalina Behavioral Health

It is a scientific fact that trauma changes the brain, but you do not have to struggle with a traumatic experience forever. The brain’s ability to form new pathways and to remain changeable with exposure to new situations and stimuli makes it resilient. Allow our team of clinical professionals to help you make the changes you need to function better after trauma exposure.

We can help you kickstart your healing process at our state-of-the-art facility. Catalina Behavioral Health uses evidence-based treatments to help you curb strong emotional reactivity and get back to a great baseline that allows you to live your life to the fullest. Reach out to our admissions staff today to learn more about how we can help you!

We Accept Most Major Insurance Providers – Call Now!

References

- Bremner J. D. (2006). Traumatic stress: effects on the brain. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 8(4), 445–461.

- Arnsten, A. F., Raskind, M. A., Taylor, F. B., & Connor, D. F. (2015). The Effects of Stress Exposure on Prefrontal Cortex: Translating Basic Research into Successful Treatments for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Neurobiology of stress, 1, 89–99.

- Koenigs, M., & Grafman, J. (2009). Posttraumatic stress disorder: the role of medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala. The Neuroscientist : a review journal bringing neurobiology, neurology and psychiatry, 15(5), 540–548.

- Aupperle, R. L., Allard, C. B., Grimes, E. M., Simmons, A. N., Flagan, T., Behrooznia, M., Cissell, S. H., Twamley, E. W., Thorp, S. R., Norman, S. B., Paulus, M. P., & Stein, M. B. (2012). Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activation during emotional anticipation and neuropsychological performance in posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of general psychiatry, 69(4), 360–371.

- Young, D. A., Chao, L., Neylan, T. C., O’Donovan, A., Metzler, T. J., & Inslicht, S. S. (2018). Association among anterior cingulate cortex volume, psychophysiological response, and PTSD diagnosis in a Veteran sample. Neurobiology of learning and memory, 155, 189–196.

- Sherin, J. E., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2011). Post-traumatic stress disorder: the neurobiological impact of psychological trauma. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 13(3), 263–278.

- Logue, M. W., van Rooij, S. J. H., Dennis, E. L., Davis, S. L., Hayes, J. P., Stevens, J. S., Densmore, M., Haswell, C. C., Ipser, J., Koch, S. B. J., Korgaonkar, M., Lebois, L. A. M., Peverill, M., Baker, J. T., Boedhoe, P. S. W., Frijling, J. L., Gruber, S. A., Harpaz-Rotem, I., Jahanshad, N., Koopowitz, S., … Morey, R. A. (2018). Smaller Hippocampal Volume in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Multisite ENIGMA-PGC Study: Subcortical Volumetry Results From Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Consortia. Biological psychiatry, 83(3), 244–253.

- Sherin, J. E., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2011). Post-traumatic stress disorder: the neurobiological impact of psychological trauma. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 13(3), 263–278.

- Alexander W. (2012). Pharmacotherapy for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder In Combat Veterans: Focus on Antidepressants and Atypical Antipsychotic Agents. P & T : a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management, 37(1), 32–38.

- Stojek, M. M., McSweeney, L. B., & Rauch, S. A. M. (2018). Neuroscience Informed Prolonged Exposure Practice: Increasing Efficiency and Efficacy Through Mechanisms. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 12, 281.